The Ancient Greeks wrote an extensive amount of drama, and tragedy and comedy emerged as a form in the 6th century BC, along with mixes of tragedy and comedy such as satyr (sometimes referred to as tragicomedy). These forms of drama were written into plays, and were often interspersed with forms of verse such as lyric and epic poetry.

Most of what modern scholars use to analyse this ancient Greek drama comes from the work of Aristotle, the ancient Greek philosopher, and in particular his Poetics. He wrote about 'poetry', which he meant as drama (comedy, tragedy and satyr) and verse (lyric and epic). Although the section of the Poetics that deals with tragedy was written at length, the section that deals with comedy has largely been lost, although Aristotle still mentions it. He describes comedy as a representation of laughable people that involves some kind or blunder that is ultimately resolved and does not lead to disaster.

Ancient Greek comedies emerged in the 6th century BC, slightly later than tragedy, and were performed as part of a twice-annual festival in the city-state of Athens, as part of the festival of Dionysia, in the Theatre of Dionysus Eleuthereus. These early comedies, expressed in a the form of lyric verse and often sang, were used to celebrate the Greek god Dionysus, the god of wine and the patron of drama. They were usually improvised but those that were written down before they were performed are now lost.

During the Golden Age of Greek drama in the 5th century BC, comedy, along with tragedy, emerged as a more established form of drama. In his Poetics, Aristotle writes that comedy took longer to establish than tragedy because people took it less seriously. At the Dionysia festival three playwrights would offer a tetralogy consisting of three tragedies and one comedy or satyr to be judged in a competition. The comedy was regularly used to lift the spirits of the audience after watching the trilogy of tragedies. These 5th century BC comedies are regarded as Old Comedy (archaia).

The most important Old Comedy dramatist from the Golden Age was Aristophanes, and he is widely regarded as the father of comedy. Aristophanes remarked that, despite the fact that comedies were taken less seriously by most people, they were actually more difficult to write than tragedies and declared that his comic plays were written for an intelligent audience. Old Comedy was a complex and sophisticated dramatic form that incorporated many approaches to humour and entertainment, such as satire and burlesque, but often purposefully descended into farce. It accommodated light entertainment, puns, buffoonery, obscenities, absurd plots and invented words with hauntingly beautiful lyrics and a formal, dramatic structure.

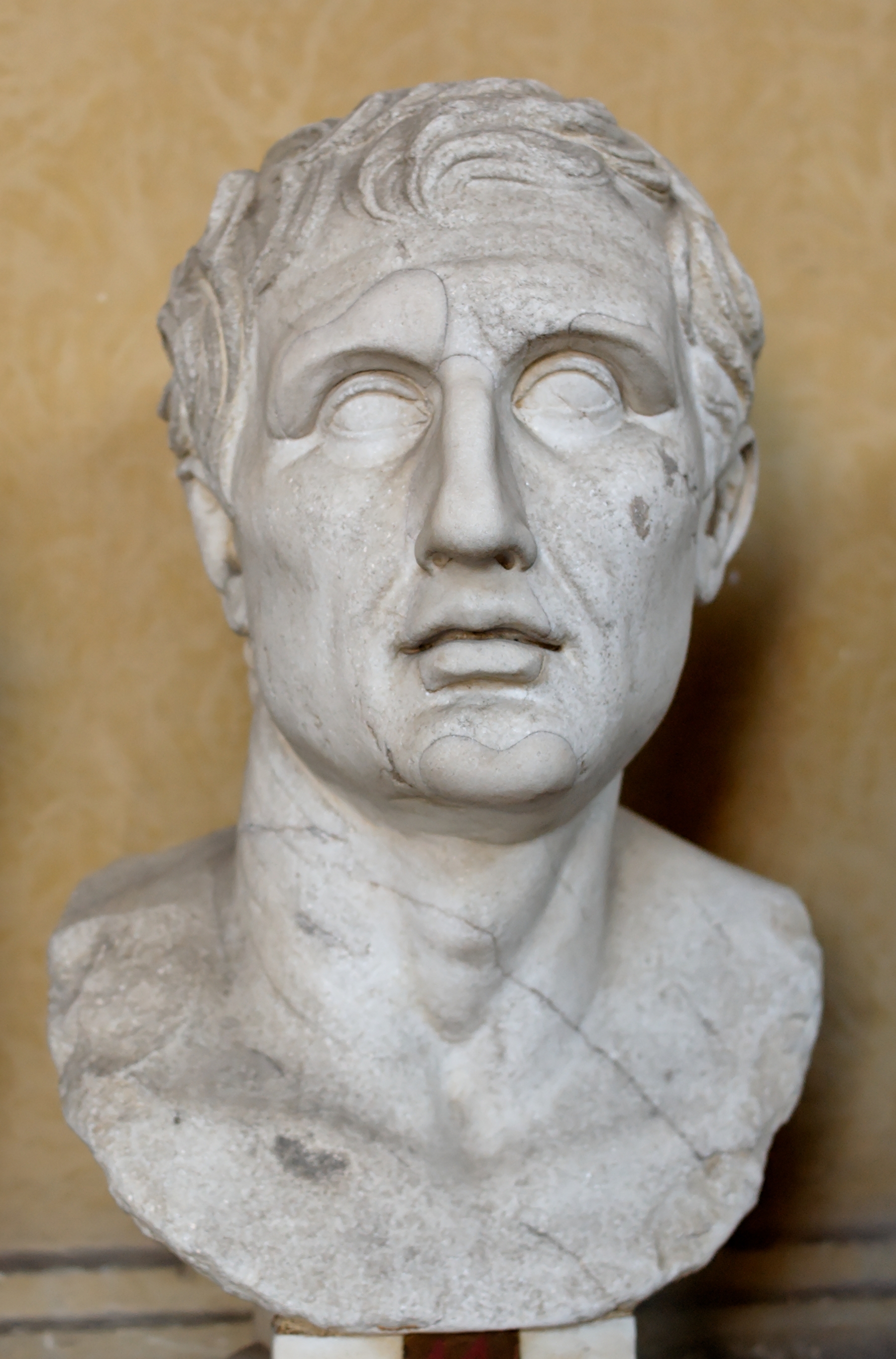

|

| Aristophanes |

The play ends with the exodus. Usually the majoy confrontation of the play (the agon) between the good and bad characters is resolved in favour of the good long before the end of the play. The rest of the play then deals with farcical consequences in a succession of loosely connected scenes. The exodus is thus usually a farcical anti-climax; the dramatic tension is released early, allowing for a holiday feeling through the rest of the play which allows the audience to relax in uncomplicated enjoyment to watch the spectacle. The ending usually saw the actors and chorus dance and sing and celebrate the hero's victory with a sexual conquest and a wedding, thus providing a joyous sense of closure.

The comic hero is resourceful and independent-minded. They have ingenuity and shrewdness but are often subjected to corrupt leaders and unreliable neighbours. Typically they devise a complicated and highly fanciful escape from an intolerable situation. Aristophanes used his comedies to parody the characters in the preceding tragedies, and other famous figures, both historical and mythological. He caricatured leading figures in the arts, such as the tragic playwright Euripides; leading figures in politics, such as the statesman Cleon; leading figures in academia, such as the philosopher Socrates; and mythological heroes, such as Heracles. Aristophanes used the conventions of comic burlesque to caricature the manner of the serious tragedies by treating famous subjects in a ludicrous way. The relaxation in standards of behaviour permitted during the holiday spirit, associated with the festival of Dionysus, led to Old Comedy being notorious for using an abundance of scatological and sexual innuendo, obscenties and crude jokes.

|

| Comedy mask |

Similarly the masks worn by the actors in Old Comedy were often caricatures of real people, often distorted into still recognisable, but ridiculous, parodies. The actors' wore costumes that were deliberately bawdy; the male characters had tights with grotesque padding and phalluses in their crotches and the female characters, played by male actors, wore overly feminine long, saffron tunics, to highlight the obvious cross-dressing of the man. Costumes were also used to mock famous characters, such as Dionysus, the god of wine and festival, appearing onstage with the lion skin cloak that usually characterised Heracles, the legendary, serious Greek hero

Old Comedies are also categorised by self-mocking theatre, where members of the audience, other comic playwrights and the writer of the play themselves were frequently mocked. Audience members could be mocked for physical deformities, ugliness, diseases, perversions, bad manners, dishonesty, cowardice in battle and clumsiness. Foreigners, such as Spartans, Scythians, Persians, Boeotians and Megarians, would often appear in comedies, hopelessly mispronouncing Greek, and specifically Athenian, words and phrases. Other comic playwrights were mocked for their failures according to the writer of the play's own opinion, and Aristophanes regularly caricatured his comic rivals Hermippus and Eupolis in his plays. Writers also parodied themselves in their plays with self-mocking jokes.

Aristophanes took on the role of teacher (didaskalos) in his comic plays, and it was conventional in Old Comedy for the Chorus to speak on behalf of the playwright during their address to the audience (the parabasis), usually at the beginning or end of the play. The Chorus were therefore elevated in Old Comedy, and were accompanied by musical extravaganza and greater expenditure on costumes, training and maintenance.

In the later 5th Century BC and later into the 4th Century BC, the form of comedy that scholars now refer to as Middle Comedy (mese), was developed. Middle Comedies diminished the role of the Chorus so they had a far lesser influence on the plot, and in particular public characters were not impersonated or personified onstage and instead the objects were general instead of personal. So methods of writing, political ideas, belief systems, personality traits and characteristics were mocked instead of poltical or mythological figures. Middle Comedies also started the tradition of using stock characters in plays, instead of historical, specific figures. So revellers, soldiers, philosophers, courtesans, cooks and parasites were produced as a representation of their profession, rather than as an actual famous character.

Less is known of Middle Comedy than Old or New Comedy; it is seen as a bridge between the two. Few full Middle Comedies remain; they mainly only in the fragments of the Middle Comedy playwright Athenaeus of Naucratis, who wrote with mainly early stock characters. However, there is some evidence that Middle Comedies were being performed in parts of southern Italy in this time, suggesting they had considerable literary and social influence.

New Comedy (nea) emerged in the late 4th century and 3rd Century BC. The three most famous and best known playwrights belonging to this genre is Menander.

|

| Menander |

Menander wrote supremely civilised and sophisticated New Comedy plays, characterised as mostly less farcical and satirical than the Old Comedies. The de-emphasis of the grotesque, whether in the form of choruses, humour or spectacle, opened the way for increased representation of daily life and the foibles of recognisable character types.

Menander's comedies were more about the fears of ordinary people, their personal relationships, family life and social mishaps rather than public, historical or mythological figures. Menander admired the tragic dramatist Euripides, and imitated his keen observation of practical life, his analysis of the emotions and his fondness for moral maxims, but in a humourous way. Menander departed from the Athenian setting or covered mythological themes and subjects that Aristophanes used in his Old Comedies; New Comedy plays were seldom placed in a setting other than their everyday world. Gods and goddesses were personified abstractions who rarely appeared in the plays and there were generally no miracles or metamorphoses.

Menander was a student of the philosopher Theophrastus, who wrote about thirty character types in his work The Characters. Theophrastus wrote that each type was said to be an illustration of an individual who represents a group, characterised by their most prominent trait. The character types were; Insincere, Offensive, Petty Ambition, Flaterrer, Hapless, Stingy, Garrulous, Officious, Show-Off, Boor, Absent-Minded, Arrogant, Complacent, Unsociable, Coward, Without Moral Feeling, Unsociable, Oligarchical, Talkative, Supersititious, Late Learner, Fabricator, Faultfinder, Slanderer, Shamelessly Greedy, Suspicious, Lover of Bad Company, Pennypincher, Repulsive, Basely Covetous Man, Unpleasant.

Menander drew from these stock characters for his plays. The cast of his plays included minor characters such as cooks or parasites who introduced familiar jokes and recognisable patterns of speech. A key stock character in his plays was the 'senex iratus', or the 'angry old man', who was a domineering parent who tries to thwart his child from achieving wedded happiness but who is often led into the same follies for which he has reproves his children; the bragging soldier who talked about the number of enemies he killed and how well he'd treat a woman; and the kind shrewd prostitute who hides her softness of heart behind a facade of toughness ('tart with a heart'). Menander gave stereotype characters a sense that they were character types. In his comedies, they were expected to react the way they were supposed to behave but some resist. These stock characters appear as rich unlayered humans in a new dimension. He used these stereotype characters to comment on human life and depict human folly and absurdity compassionately, with wit and subtlety.

New Comedies are more like romantic and situation comedies and comedy of errors than the burlesque and satirical Old Comedies. Menander introduced the 5-act that was been widely used in many later plays. Old Comedies had choral interludes but in New Comedies there was dialogue with song and the chorus was greatly diminished. The action of his plays had breaks, thus breaking up each act and allowing for a smooth and effective development of the play through the acts.

No comments:

Post a Comment