The Ancient Greeks wrote an extensive amount of drama, expressed in the form of plays and often interspersed with forms of verse such as lyric and epic poetry. Most of what modern scholars use to analyse this ancient Greek drama comes from the work of Aristotle, the ancient Greek philosopher, and in particular his Poetics. Although this was written in the 4th century BC, around a century after the Golden Age of Greek drama and nearly two hundred years after the earliest forms of drama, Aristotle had first-hand documentation from theatre performances in Athens, which is lost to modern scholars. His Poetics is the earliest surviving work of dramatic and literary theory. He offers an account of 'poetry' (this means tragedy, comedy and satyr drama, as well as lyric and epic poetry) whereby he explains their basic elements and genres. His analysis of tragedy is particularly dense and interesting.

Aristotle writes that tragedy is represented in part by spoken action (drama) and in part by song (lyric poetry) or extended verse (epic poetry). Tragedy consists of six parts which Aristotle enumerates in order of importance, beginning with the most essential and ending with the least: plot (mythos), character (ethos), thought (dianoia), diction (lexis), melody (melos) and spectacle (opsis).

The plot refers to the order of events that happen in the play. The Aristotelean tragic plots should be about serious, complete action which has magnitude. They should involve a change of fortune where good fortune proceeds to bad and there is a high degree of suffering for the protagonist that ends in physical harm or death. The actions should follow naturally from actions that precede them, but plot points that appear by surprise or seeming coincidence and are only afterwards seen as plausible are satisfying for the audience.

Aristotle writes that characters should have a tragical accident happens to them because of a mistake they make (hamartia), or a flaw they have, instead of things that might happen anyway. This allows for a better moral lesson for the audience. The tragic hero should be: virtuous at first, so that people can learn a moral lesson that loss of virtue leads to suffering; appropriate, so that a wise, worldly character is unlikely to be very young; and consistent, so that the audience is not confused by unexplained shifts in behaviour, such as an academic man acting foolishly. The Aristotelean tragic hero is thus a virtuous man, usually in a position of power, who, through misfortune and errors of judgement arising from his tragic flaw, is brought from prosperity to adversity. A popular tragic flaw to portray in a hero was hubris, which meant pride. Hubris indicated an overestimation of one's competence or capabilities which meant a loss of contact with reality that lead to nemesis, or downfall. This predates the modern adage of 'pride comes before a fall'.

Other elements of tragedy include thought, which is the spoken reasoning of characters so they can explain their inner beliefs to an audience; diction, which is the type of speech used in dialogue between characters, and should reflect that character's status, occupation and morality; melody, which is the role of the Chorus, who form an integral part of informing people of the action; and the spectacle, which refers to the set, costumes and props in the play.

Aristotle declares that tragedy is performed mainly to invoke catharsis in the audience, which is understood as the emotions of pity and fear that are brought to spectators after viewing a tale of human flaws leading to suffering. So when a character has a reversal of fortune (peripeteia), at first he suffers (pathos), but then he realises the cause of his misery (anagnorisis) which brings about pity in the audience (catharsis), and acknowledgement of a moral point or lesson.

Aristotle notes that the earliest dramas were expressed as tragedies, in the 6th century BC. In this time, tragedies were performed as part of a twice-annual festival in the city-state of Athens. The festival was called Dionysia, and took place once in winter and once in spring. This festival honoured the Greek god Dionysus who was the god of wine and fertility and the patron of drama. Comedy and satyr play also emerged as genres, although slightly later.

These tragedies at Dionysia were written as part of religious devotion but also to foster both loyalty and competition between the rival Athenian tribes. In this time they would have been relatively simple plays, with only one actor speaking in monologue. They were often put to music and there would have been a group of around fifty men and boys, known as the Chorus, who danced and sang in a circle and offered up hymns in honour of Dionysus. The songs were called a dithyramb, and originally they were improvised, but later they were written down before performance. Sometimes these dithyrambs were serious in tone, and written in the prosaic iambic trimeter, but later they became briefer and sometimes burlesque in tone. These satyric versions of the dithyramb were written in trochaic tetrameter. Forms of satyr and comedy formed as a distinct drama from the less serious dithyrambs.

These early tragedies were written to be played only once, at the festival, and were performed at the Theatre of Dionysus Eleuthereus, which was an open-air theatre in Athens. The early theatre would have been very simple, comprising a flat orchestra with a few rows of wooden benches set into the hill. The performance space was a simple circula space, known as the orchestra, where the chorus danced and sang. Most of the early tragedies written here are lost.

|

| Modern-day remains of the Theatre of Dionysus |

Athens entered the Hellenistic period, which is regarded as the Golden Age of Greek drama. Theatre became formalised as an even greater part of Athenian culture and the twice-annual Dionysia became even more of a fierce competition between playwrights. Although tragedy flourished in this time, so too did comedy and satyr. At the Dionysia festival three playwrights would offer a tetralogy consisting of three tragedies and one satyr or comedy to be judged in a competition.

|

| Depictions of masks worn by tragic actors |

Only one complete tetralogy has survived from this time, the Oresteia of Aeschylus. Aeschylus is often described as the father of tragedy, and he is credited with inventing the trilogy, a series of three tragedies that tell one long story, and the final satyr or comedy performed afterwards to lift the spirits of the spectators. Aeschlyus was part of the evolution of tragedy, whereby dialogue, contrasts and theatrical effects were introduced, along with a second actor to increase conflict. Aeschlyus' plays were full of strict morality and intense religiosity. Zeus, the god of sky and thunder, always has the role of ethical thinking and action, and the music and lyrics used by the chorus use traditional rhythmic and melodic structures.

Aeschylus would have been in competition with the younger Sophocles, who introduced a third actor into his plays to increase plot complexity. He also introduced scenery and scenes by using a backdrop, which hung or stood behind the orchestra, which also served as an area where actors could change their costumes. It was known as the skênê (from which the word 'scene' derives), and the death of a character from then on would be heard from behind the skênê. After a death, the ekkyklêma would be used, which was a wheeled platform used to bring the dead characters in view of the audience. Sophocles made the chorus less important in explaining the plot, which added emphasis to character development. He focused on describing the painful realities of the human condition by not attempting to justify the events that overwhelm the heroes but instead using human characters that the audience could identify with. This is a theme that has survived throughout all literature.

The third great playwright of the time was Euripides, who was in competition with the other two. He furthered diminished the role of the chorus by having the characters sing plot points and often turning the prologue into a monologue spoken by one of the characters. He also delved more into realism, portraying his tragic heroes as more insecure than Aeschylus and Sophocles' heroes. They are more plagued by internal, psychological conflicts, rather than being resolute and assured of themselves. He was also the first playwright to use female characters, although they would still have been played by masked men. Euripides used female characters primarily to represent the irrational impulses that collide with the world of reason.

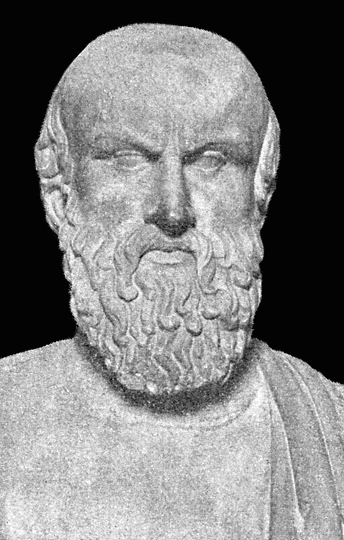

|

| Aeschylus |

|

| Sophocles |

|

| Euripides |

Many of the Golden Age Greek tragedies involved myths surrounding the epic stories of the Trojan war, and the stories of the Greek characters such as Achilles, Odysseus, Ajax, Menelaus, Agamennon, Helen and others; or the Trojan characters of Priam, Hector, Paris, Andromache and others. Others would tell the stories of legendary Greek heroes such as Heracles and his labours, Jason and the Argonauts, Perseus and the Medusa/Gorgon, Prithous and the Centauromachy, Odepius and Thebes, Orpheus and the Orphic Mysteries, Theseus and the Minotaur, Triptolemus and the Eleusinian Mysteries, and Atalanta and Hippomenes' Race (Golden apple). Often the Greek gods would be involved, such as Zeus, Hera, Hades, Poseidon, Athena, Aphrodite, Apollo, Hermes and others.